Exposition - I was born and you gotta live with the bad blood now - erg galerie - 17.04 -21.04.2023

De erg

| Actualités | |

|---|---|

| Publiée | 2023-03-30 |

Exposition

I was born and you gotta live with the bad blood now

erg galerie, Bruxelles, du 17 au 21 avril 2023

L’exposition sera accompagnée d’une table ronde dans l’auditorium de l’erg, mardi 18 avril, à partir de 14h à 18h avec Nicole Lapierre (socio-anthropologue au CNRS et autrice de Faut-il se ressembler pour s'assembler?), Nelson Bourrec Carter (artiste-réalisateur), Lucie Szechter (artiste-réalisatrice), Joanna Lorho (dessinatrice et enseignante à l’erg) and Nicolas Wouters (dessinateur-réalisateur et enseignant à l’erg).

À l’occasion de la table ronde seront projetés des extraits des films : Levittown (2018), L’Oreille décollée (2018), La mémoire de Nelly (2018)

Horaires d’ouverture de la galerie :

Lundi 17 avril : 14h-19h

Mardi 18 avril : 10h-12h / 18h-20h (vernissage)

Mercredi 19 avril : 15h-18h

Jeudi 20 avril : 15h-18h

Vendredi 21 avril : 10h-14h

Visite possible hors ouverture sur rdv : szechterlucie@gmail.com

Table ronde dans l’auditorium :

Mardi 18 avril : 14h-18h

Texte de présentation détaillé :

FR — La pensée de « l’apparentement » repose sur le paradigme suivant : « ceux qui se ressemblent appartiennent à une même famille et, inversement, les membres d’une même famille sont censés se ressembler » (Noudelmann, 2012). Construites sur cette logique, il existerait deux types de sociétés fondées sur la ressemblance. La première – excluante – rejette purement et simplement ceux et celles qui ne ressemblent pas au modèle physique institué. L’autre – incluante mais autoritaire – prône l’assimilation et encourage celles et ceux qui seraient dissemblables à gommer leurs différences pour mieux correspondre au canon dominant (Lapierre, 2020). Dès lors, comment répondre à la question « Qui es-tu ? » dans le cas précis qui nous intéresse de mise en tension entre la ressemblance physique et l’identité propre qui nous constitue en tant que personne ? Pour Judith Butler, il faut penser les identités à la lumière de l’institution et de ses normes. Quelles sont nos conditions d’apparition ? Qui a le pouvoir de nous reconnaître ou non ? Qui décrète la viabilité d’une vie en fonction de critères structurellement construits et profère le verdict : valide / invalide ; légitime / illégitime ; pur / impur ; vrai / faux ? Les œuvres des artistes invité·e·s mettent le regard à l’épreuve et questionnent, chacune à sa manière, la visibilité et sa charge normative.

Raphaël Fabre commence par poser le problème de la ressemblance à soi-même. Son autoportrait dans CNI (2017), qui n’a rien d’une image indicielle puisqu’il a été créé de toute pièce numériquement, sera pourtant validé par l’État français et institué officiellement sur sa carte d’identité. L’artiste se joue/déjoue le morphème de comparaison « comme », moteur dans les méthodes de contrôle et d’identification. Est-ce toujours lui seulement parce qu’il est physiquement semblable à lui-même ?

L’artiste thaïlandais Prapat Jiwarangsan glisse également vers la fiction dans son film Parasite Family (2021) en proposant une vision disruptive des liens familiaux. En montant ensemble d’anciens négatifs découverts dans un laboratoire de développement, il crée des filiations nouvelles. Les visages de familles riches et d’institutions, connues pour conserver le pouvoir au détriment du reste de la société thaïlandaise, perdent progressivement la face (on pense ici à Erving Goffman). Analogique, numérique, images générées par l’IA et œuvres NFT révèlent un portrait de famille monstrueux de la classe dominante.

C’est aussi sur le lien étroit entre famille et société que je m’appuie dans mon Film de bâtarde (2023), monté par Benjamin Cataliotti Valdina. Ce film de réemploi (found footage) tente de saisir l’écart à la norme en matière d’hérédité et de ressemblance en passant par la voix de la bâtardise. Les ressemblances, le patronyme, l’ADN sont d’éminents patrimoines symboliques dont ne jouissent pas les bâtard·e·s. Or, à quoi nous mène l’idéologie du même (même « sang », même « ADN ») et la croyance que le même est beau et bon quand l’établissement de ce canon infériorise et exclut certains membres de la « famille nationale » ? En cherchant à faire primer la relation sur l’héritage vertical et la production de nouveaux biens, j’invite mon père Philippe Szechter à présenter une œuvre en résonnance avec l’une des séquences de mon film L’Oreille décollée (2018), dont il était l’un des principaux acteurs. Les quatre organes de She's a replicant, isn't she? (2023), entre ex-voto et prothèses, font quant à eux parler la surface d’un corps jusqu’à présent restée passive.

C’est également en passant par la parole qu’agit Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński dans son film Unearthing. In Conversation (2017). Présente dans son propre cadre, l’artiste soutient notre regard et montre des portraits de l'ethnographe et missionnaire Paul Schebesta posant avec des habitants de l'ancien Congo belge au début du vingtième siècle. En transformant les archives (découpe, collage), elle révèle la cécité du regard colonial et sa capacité néfaste à placer des individus, jugés physiquement dissemblables aux colonisateurs, sous les radars du visible et donc de l’entendement. Le film offre un lieu pour panser et repenser une socialité entre sujets, au sens philosophique du terme, à partir du passé. À rebours de l’objectification des corps, elle restitue par l’image et le montage ce que Judith Butler (2010) nomme la « reconnaissabilité » des personnes et qui précède tout acte de reconnaissance.

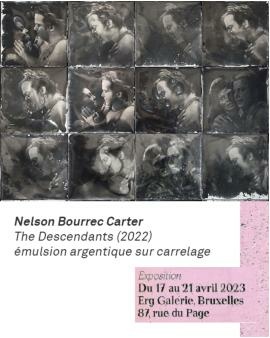

Dans une certaine continuité, Nelson Bourrec Carter interroge non pas l’invisibilisation mais, au contraire, la complexité d’une soudaine exposition : celle du premier baiser interracial diffusé à la télévision américaine en 1968. Ce baiser, qui pourrait être la représentation d’une mixité enfin assumée dans l’espace médiatique, s’avère, dans le scénario de l’épisode de Star Trek auquel il appartient, le résultat d’une manipulation. La possibilité d’une relation basée sur d’autres motifs que des critères de ressemblance physique (être noir ou blanc) prévaut in fine sur d’autres ressorts fictionnels qui auraient pu unir les deux personnages (le désir ou l’amour, par exemple). Ainsi, l’image est-elle à double tranchant. Elle offre enfin la possibilité de pouvoir imaginer une union interraciale dans l’imaginaire collectif, donc les conditions d’une « reconnaissabilité », tout en refusant de la légitimer. Dans l’œuvre, l’émulsion argentique du baiser se répète, à la fois identique et sensiblement différente, comme pour signifier sa dualité intrinsèque : révéler, donc attester d’une existence là où l’image était jusqu’à présent manquante, tout en l’abimant via la condamnation morale de ce qu’elle représente.

La vidéo Camgirl (2022) de Mateo Aureille, Ambre Fraisse et Lou Respinger travaille elle aussi la question de l’image, du désir et de l’auto-présentation (être responsable des conditions de sa propre apparition) sur Chatroulette. Épousant la transformation physique du personnage principal, la scène de reconnaissance évolue et laisse place à la sidération. N’étant ni le même, ni une autre, les regards masculins des spectateurs du site de messagerie instantanée semblent échouer à circonscrire ce corps non identifiable. En échappant au pouvoir de l’apparentement, camgirl provoque des réactions où la haine et le désir semblent étroitement liés.

EN — "Likeness" thinking is based on the paradigm that "those who look alike belong to the same family and, reciprocally, members of the same family are supposed to look alike" (Noudelmann, 2012). According to this logic, there would be two types of societies based on similarity. The first - exclusionary - rejects outright those who do not resemble the instituted physical model. The other - inclusive but authoritarian - advocates assimilation and encourages those who are dissimilar to erase their differences in order to better fit the dominant canon (Lapierre, 2020). So, how can we answer the question "Who are you?" in the specific case we are interested in, which involves a tension between physical resemblance and the very identity that constitutes us as a person? For Judith Butler, identities must be thought in the light of the institution and its norms. Under what circumstances are we deemed visible ? Who has the power to acknowledge us or not? Who dictates the viability of a life required to be aligned with socially constructed criteria, and proclaims the verdict: valid / invalid; legitimate / illegitimate; pure / impure; true / false? The works of the invited artists put the gaze under test and question, each in its own way, visibility and its normative charge.

Raphaël Fabre begins by posing the problem of resemblance to oneself. His self-portrait in CNI (2017), which has nothing to do with an indexical image since it was created entirely digitally, will nevertheless be validated by the French State and officially established on his identity card. The artist plays with the morpheme of comparison " like ", a driving factor in the methods of control and identification. Is it still him, solely because of the physical similarity to his true self?

Thai artist Prapat Jiwarangsan also slips into fiction in his film Parasite Family (2021) by offering a disruptive vision of family ties. By assembling old negatives discovered in a photo lab, he creates new filiations. The faces of wealthy families and institutions, known to retain power at the expense of the rest of Thai society, gradually lose face (one thinks here of Erving Goffman). Analog, digital, AI-generated images and NFT works reveal a horrific family portrait of the ruling class.

It is also rely on the close link between family and society in my Film de Bâtarde (2023), edited by Benjamin Cataliotti Valdina. This found footage film attempts to capture the deviation from the norm in terms of heredity and resemblance through the voice of bastardy. The resemblance, the family name, the DNA are eminent symbolic legacies that the so-called "illegitimate children" do not enjoy. But where does the ideology of sameness (same "blood", same "DNA") and the belief that sameness is beautiful and good lead us when the establishment of this canon inferiorizes and excludes certain members of the "national family"? In seeking to prioritize relationships over vertical inheritance and the production of new goods, I’m inviting my father Philippe Szechter to present a work that resonates with one of the sequences in my film L'Oreille décollée (2018), in which he was one of the main actors. The four organs of She's a replicant, isn't she? (2023), between the ex-voto and the prosthesis, make the surface of a body that until now had remained passive speak.

It is also through the spoken word that Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński acts in her film Unearthing. In Conversation (2017). She is present in her own frame and holds our gaze. Her hands show portraits of ethnographer and missionary Paul Schebesta posing with inhabitants of the ex-Belgian Congo in the early twentieth century. By transforming the archives (cutting, collage), she reveals the blindness of the colonial gaze and its harmful ability to place individuals, deemed physically dissimilar to the colonizers, away from the spectrum of the visible and the intelligible. The film offers a place to heal and rethink a sociality between subjects, in the philosophical sense of the term, from the past. In contrast to the objectification of bodies, it restores through images and editing what Judith Butler (2010) calls the "recognizability" of people and which precedes any act of recognition.

In a certain continuity, Nelson Bourrec Carter questions not the invisibilization but, on the contrary, the complexity of a sudden exposure: that of the first interracial kiss broadcast on American television in 1968. This kiss, which could be the representation of an understanding, of a union finally acknowledged in the media space, turns out, in the scenario of the Star Trek episode to which it belongs, to be the result of a manipulation. The possibility of a relationship based on other motives than physical resemblance criteria (being black or white) prevails in fine over other fictional motives that could have united the two characters (desire or love, for example). Thus, the image is double-edged, it finally offers the possibility of being able to imagine an interracial union in the collective imagination, that is to say the conditions of a recognizability, while refusing to legitimize it. In the artwork, the silver emulsion of the kiss is repeated, at the same time identical and significantly different, as if to signify its intrinsic duality: to reveal, thus attesting to an existence where the image was until now missing, while damaging it via the moral condemnation of what it represents.

The video Camgirl (2022) by Mateo Aureille, Ambre Fraisse and Lou Respinger also delves on the question of image and desire and self-representation (being responsible for the conditions of one's own apparition) on Chatroulette. Following the physical transformation of the main character, the initial stage of recognition evolves and gives way to disbelief. Being neither the same, nor another, the male gaze fails to define this unidentifiable body. By escaping the power of “likeness”, Camgirl provokes reactions where hate and desire seem tightly intertwined.

Remerciements : l’équipe de l’erg, Sammy Del Gallo, Joanna Lorho et Laurence Rassel pour leur accueil, les artistes pour leur confiance, Bérangère Portella (Amanite) pour l’affiche, Coralie Maurin, Sylvie Coulon, Nelson Bourrec Carter, Julien Stout, Anne-Laure Mercier, Raphaël Duizend, Marie Desaunay, Benjamin Cataliotti Valdina et Thomas Etcherbarne.

Lucie Szechter, commissaire de l’exposition